CI TL;DR — better every day

- Continuous Improvement (CI) is the relentless, organisation-wide pursuit of small, daily gains that compound into breakthrough performance.

- Why adopt? Transforms firefighting into proactive learning, boosting quality, speed, cost, and engagement simultaneously.

- Key elements: Hoshin strategy deployment, daily management boards, Gemba walks, idea systems, and Kaizen events.

- Cultural enablers: respect for people, psychological safety, leadership modeling, rapid feedback and recognition loops.

- Road-map: Set true-north vision → train teams → map processes → run PDCA cycles → measure outcomes → share wins → repeat.

- Toolkit: CI maturity audit, idea funnel board, Kaizen charter, PDCA template, and success story template provided in the guide.

Continuous improvement (CI) is the ongoing effort to improve products, services, or processes through incremental (and sometimes breakthrough) changes. In practice, CI aims to eliminate waste and increase efficiency, quality, and customer satisfaction. The Lean Enterprise Institute defines CI (also known as Kaizen) as a “philosophy and set of principles that focuses on making small, incremental changes” to processes. Originating at Toyota in the 1950s, the Lean philosophy saw that steady, incremental gains could add up to dramatic improvements in performance. In modern organizations, CI is pursued as a strategy for process optimization and competitiveness. By embedding continuous improvement into strategy and daily work, businesses can adapt more quickly, reduce costs, and innovate alongside changing customer needs. As ASQ notes, CI efforts use methods like Lean, Six Sigma and TQM to involve employees, measure processes, and reduce variation, defects, and cycle times

The Strategic Role of CI in Organizations

Adopting CI is more than a one-time project; it is a strategic approach woven into the organization’s goals and processes. A continuous improvement strategy ensures that improvement efforts align with business objectives – for example, increasing productivity, cutting lead times, or boosting quality. Lean thinking teaches that strategy and operations must be linked: Toyota’s culture of kaizen means every team continuously seeks better ways to meet customer needs and strategic targets. When CI is strategic, it can drive innovation and change by unlocking employee creativity and focusing on customer value. Harvard Business Review authors Chandrasekaran and Toussaint note that health systems applying Toyota Production System (TPS) principles scored “impressive gains” in outcomes and satisfaction by redesigning processes to eliminate waste. In short, CI as strategy helps organizations stay competitive by systematically optimizing processes (process optimization) rather than relying on ad hoc fixes.

Implementing CI strategically also means building it into the organization’s management systems. For example, successful companies use Hoshin Kanri (policy deployment) to translate high-level objectives into daily improvement targets. In this way, continuous improvement becomes part of how the company operates, not just an occasional activity. As ASQ observes, popular CI methods emphasize employee involvement and teamwork, helping to align improvements with the company’s strategic needs. In a true CI strategy, leaders set clear goals (e.g. “reduce defects by 50%”), provide resources and training, and ensure that front-line teams have both the autonomy and the data they need to pursue improvements effectively. This strategic role of CI ultimately ensures that the effort to improve processes supports the overall mission and vision of the organization.

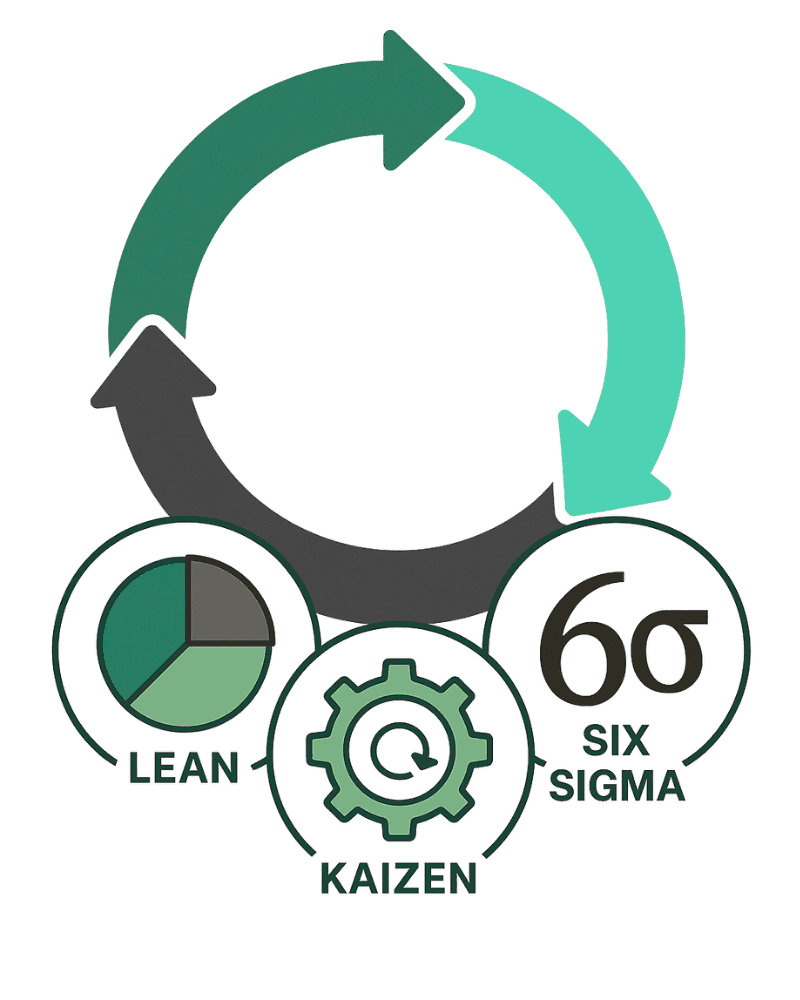

Foundational Frameworks: Lean, Kaizen, and Six Sigma

Organizations use several related frameworks to guide continuous improvement. Three foundational approaches are Lean, Kaizen, and Six Sigma. Each has its own history and focus, but they overlap and complement one another in practice.

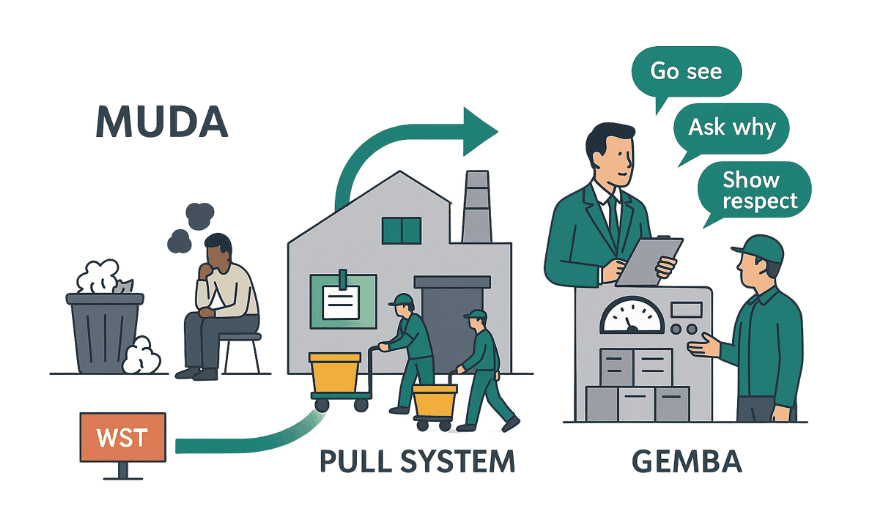

Lean

Lean originated with Toyota’s Production System (TPS). It centers on eliminating waste (muda) and creating value for the customer by optimizing flow. In Lean philosophy, continuous improvement is a core principle. Lean practitioners strive to make processes as smooth as possible (flow) and to use a pull system so that work is done only on demand. Lean also emphasizes respect for people, with every employee encouraged to spot and solve problems. For example, Toyota’s Fujio Cho famously advised Lean leaders to “Go see, ask why, show respect” on the shop floor. This means managers should regularly walk the gemba (the real place where work happens) and engage with workers to understand issues.

A lean management culture goes hand-in-hand with CI. It involves leaders who support problem solving, and front-line employees who are empowered to improve their own work. As David Verble of the Lean Enterprise Institute explains, a true Lean culture is essentially a “problem-solving culture” built on shared assumptions about improvement, not just a set of tools. In Lean, continuous improvement is not an isolated event but an ongoing mindset: Toyota encourages every worker to make and submit improvement suggestions (kaizen ideas) every year, with recognition and reward for successful ideas. In short, Lean provides both the culture (respect, teamwork) and the principles (waste reduction, flow, pull) that guide continuous improvement activities.

Kaizen

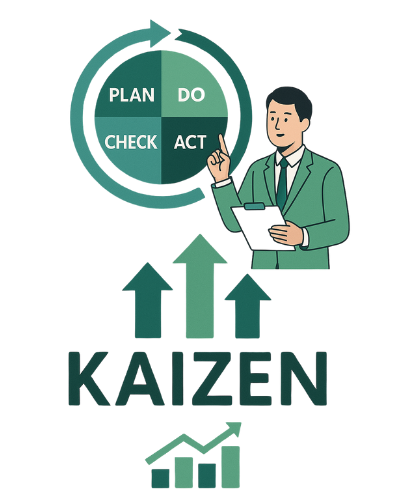

Kaizen is the Japanese word for “continuous improvement” and represents the core philosophy behind Lean improvement. A Kaizen approach focuses on small, incremental changes rather than big overhauls. In practice, Kaizen encourages everyone in the organization to look for ways to improve their work continually. As the Lean Enterprise Institute notes, the Kaizen philosophy “has been successfully implemented in various industries… to reduce waste and increase efficiency” by involving employees at all levels. Typical Kaizen activities include short, rapid improvement events (often called kaizen blitzes) and daily suggestion systems.

The Kaizen process is often structured using Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycles. This means identifying a problem or opportunity, planning a change, testing it, checking the results, and then iterating. Importantly, Kaizen emphasizes that improvements should be practical and quickly implementable. According to the Lean Enterprise Institute, Kaizen leads to “significant long-term benefits” by making many small improvements over time. It is a philosophy that underscores continuous process optimization: over weeks and months, these small changes accumulate into much larger performance gains.

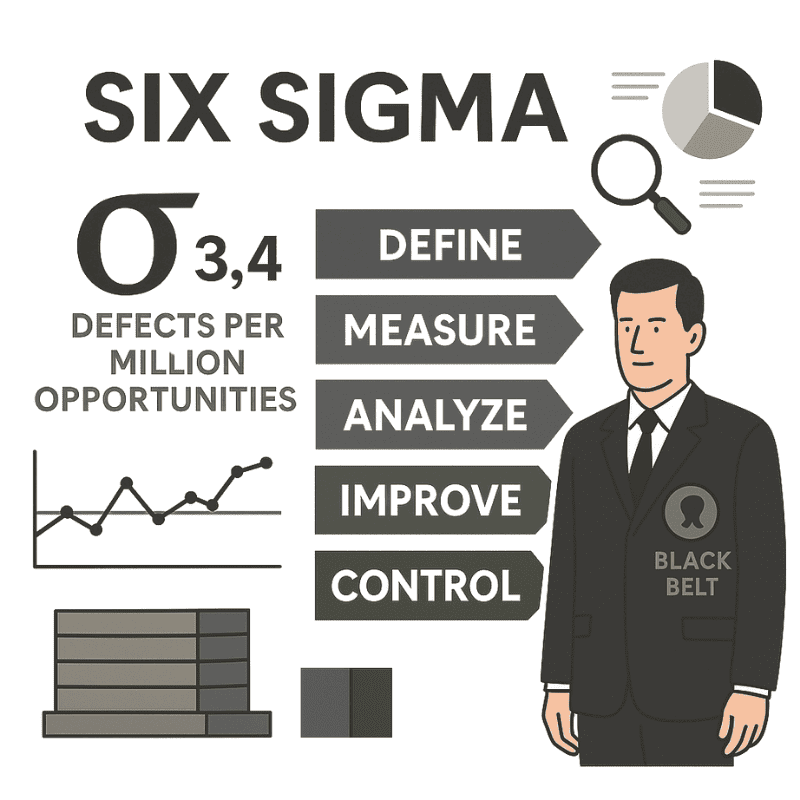

Six Sigma

Six Sigma is a methodology that emerged in the 1980s (pioneered by Motorola) with the goal of reducing defects and process variation using data-driven methods. It became famous under Jack Welch at GE, but its roots are in statistical quality control. Six Sigma’s ultimate target is extremely low defect rates (3.4 defects per million opportunities). Central to Six Sigma is the DMAIC cycle – Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control – which provides a structured problem-solving roadmap.

Six Sigma projects are often led by trained specialists (Black Belts, Green Belts) who use statistical tools to identify root causes of quality problems. The Define phase sets the project goals and customer requirements; Measure collects data on current performance; Analyze identifies root causes of defects; Improve implements solutions; and Control ensures the gains are sustained. ASQ notes that DMAIC is a “data-driven quality strategy used to improve processes” and is integral to Six Sigma initiatives. Many of the “Six Sigma tools” – such as control charts, Pareto analysis, and cause-and-effect diagrams – are now widely used across industries for CI.

In practice, organizations often blend Lean and Six Sigma into Lean Six Sigma. This combines Lean’s focus on speed and flow (waste elimination) with Six Sigma’s emphasis on variation reduction and data. For example, Lean Six Sigma principles include focusing on customer needs, eliminating non-value activities, continuous improvement, and data-driven decision-making. Companies that have embraced both tend to see stronger cultural change and measurable results: Motorola famously documented over $16 billion in savings from its Six Sigma efforts, largely by systematically reducing defects and waste. Ultimately, Lean, Kaizen, and Six Sigma are three perspectives on CI that reinforce each other: Lean/Kaizen builds a culture of small daily improvements, while Six Sigma provides rigorous tools and metrics to tackle bigger quality challenges.

Tools and Techniques Used in CI

Continuous improvement relies on a variety of tools and methods for diagnosing problems, testing solutions, and measuring results. Key CI tools include process improvement cycles, root-cause techniques, workplace practices, and statistical controls. The following are some widely used CI tools:

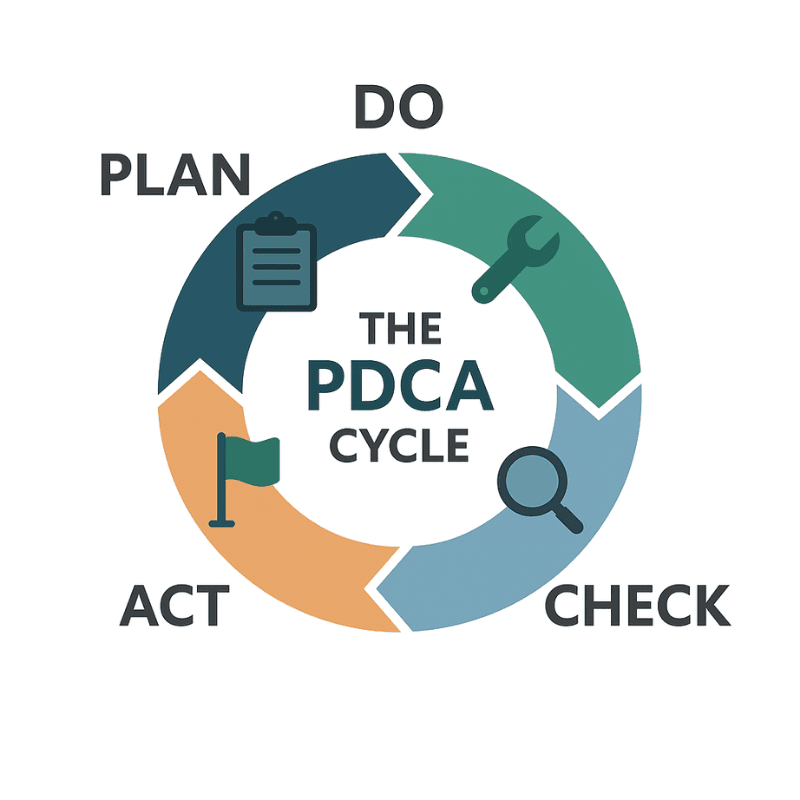

PDCA (Plan-Do-Check-Act) Cycle

The PDCA cycle is a four-step iterative model for carrying out change. It is often used to structure Kaizen activities. The steps are:

- Plan: Identify an opportunity and plan a change (set objectives and metrics).

- Do: Implement the change on a small scale to test it.

- Check: Review and analyze the test results to see what was learned.

- Act: If the change was successful, implement it broadly; if not, refine the plan and repeat the cycle.

Just as a circle has no end, PDCA should be repeated indefinitely for continuous improvement. By cycling through PDCA, teams constantly plan new improvements based on what they learn from previous tests. For example, a factory might use PDCA every week to reduce defects on a production line: plan a tweak to a machine, test it overnight, check defect rates, and then standardize the improvement or try another change.

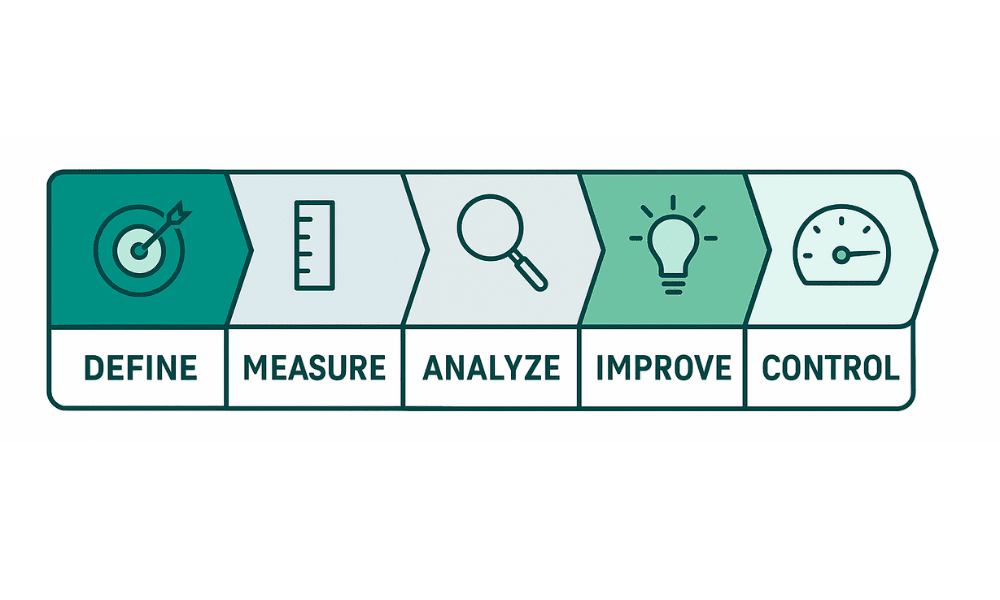

DMAIC (Define-Measure-Analyze-Improve-Control)

In Six Sigma projects, the DMAIC process provides a similar structured cycle. It stands for Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control. ASQ explains that DMAIC is “a data-driven quality strategy used to improve processes” and is part of Six Sigma. The five phases are:

- Define: Formally define the problem or opportunity, project goals, and customer requirements. This often involves a project charter, voice-of-customer analysis, and mapping the current process flow.

- Measure: Collect data and measure current process performance (baseline). For example, use flowcharts, process capability analysis, or Pareto charts to quantify defects or process metrics.

- Analyze: Determine the root causes of variation or defects. Tools like root cause analysis, fishbone diagrams, and statistical tests are used here.

- Improve: Implement and test solutions to address the root causes. This may involve redesigning parts of the process, piloting new methods, or running experiments.

- Control: Put controls in place to sustain improvements. This means standardizing the improved process and monitoring it (for example, using control charts) to ensure gains are maintained over time.

Together, these steps guide a team from problem identification to long-term improvement, combining both problem-solving and statistical control techniques. While DMAIC was developed for Six Sigma, many organizations apply it (or variants of it) whenever they have a complex process problem.

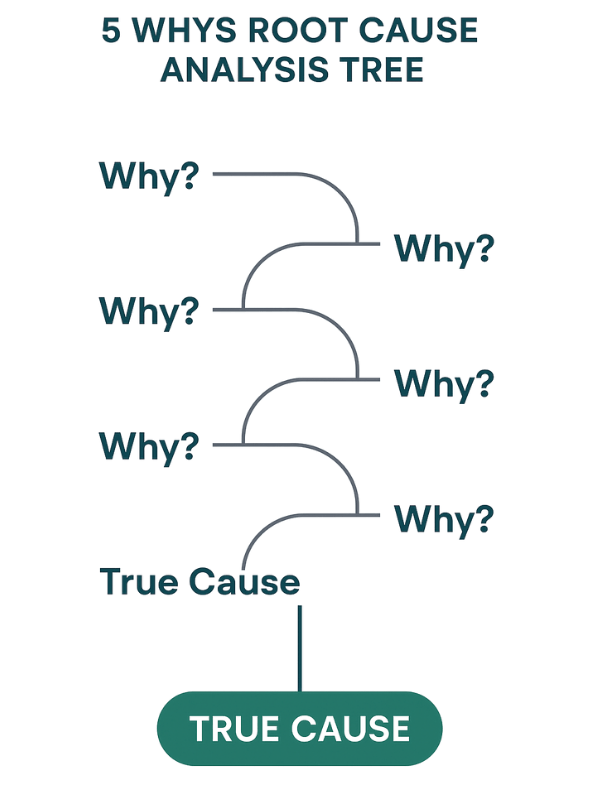

5 Whys

The 5 Whys is a simple but powerful root-cause analysis technique from Toyota’s toolkit. As Toyota founder Sakichi Toyoda introduced, you ask “Why?” about a problem and then ask “Why?” about each answer, typically five times, to drill down to the underlying cause. For example, if a machine stopped, you might ask: “Why did the machine stop?” (Because a fuse blew.) “Why did the fuse blow?” (Because the motor overheated.) “Why did it overheat?” and so on, until you hit a fixable root cause like inadequate cooling. The 5 Whys embodies the Lean principle that problems should be probed gently and factually until the true cause is found. Importantly, teams avoid blaming individuals; the goal is to learn, not to assign fault. Today, many companies use the 5 Whys in Kaizen events and daily problem-solving because it is easy to apply on the shop floor or in offices without complex statistics.

Gemba Walks

A Gemba Walk (from the Japanese “Gemba,” meaning “the real place”) is a Lean practice for leaders and teams. The idea is simple: go to the place where value is created (for example, the factory floor, service desk, or office where work happens) and observe processes directly. By walking the floor and talking to people, leaders see the actual conditions, ask questions, and gather ideas that might be missed by staying in an office. As one Lean guide explains, managers often have not seen the process or spoken to customers; Gemba walks bridge that gap. Fujio Cho of Toyota said that good leaders should “go see, ask why, and show respect” during such walks. In practice, a Gemba walk might involve a manager spending a few hours each week in a work cell, mapping the flow, noting waste (like delays or defects), and asking frontline workers for suggestions. This hands-on approach makes improvement immediate and visible, and demonstrates leadership commitment to CI.

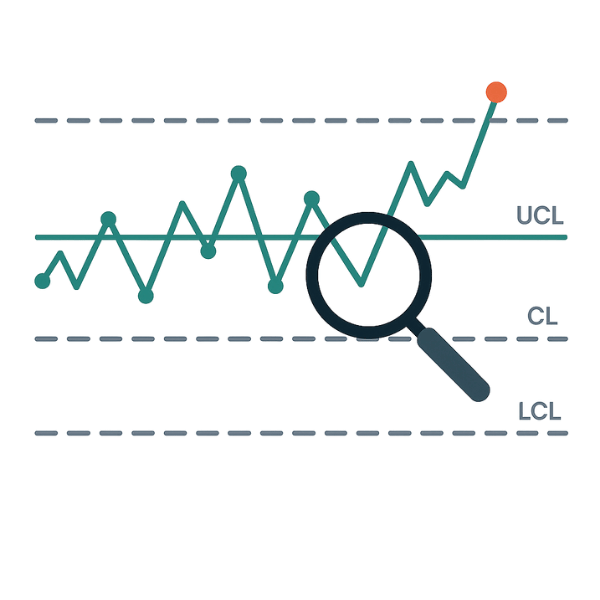

Control Charts

Control charts (also called Shewhart charts) are a fundamental tool of Statistical Process Control (SPC) and continuous improvement. A control chart plots process data (such as cycle time or defect counts) over time, with a center line (the process average) and upper/lower control limits determined by historical variation. By comparing current data to these limits, teams can tell if the process is stable (only common-cause variation) or if special-cause variation has occurred. For example, in a manufacturing line, if daily defect counts suddenly exceed the upper control limit, an investigation would be triggered to find the unusual cause (maybe a worn tool). Control charts enable continuous monitoring: any out-of-control signal leads to immediate problem-solving. This data-driven method ensures that CI work is focused where variation is truly problematic. Control charts are considered one of the “seven basic quality tools” and are used in many industries, from factories to service centers.

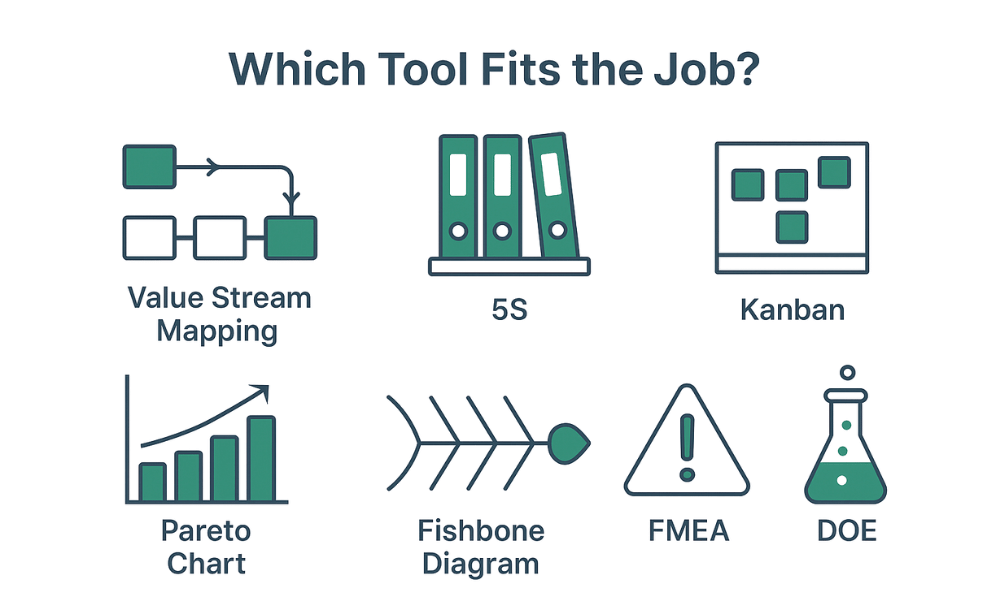

Other CI Tools

Beyond these, many other techniques support CI. Common examples include value stream mapping (visualizing end-to-end process flow to identify waste), 5S workplace organization (sorting, setting in order, shining, standardizing, sustaining), Kanban systems (visual signals to control flow), Pareto charts (highlighting the “vital few” causes), and Ishikawa (fishbone) diagrams (categorizing potential causes of a problem). For data analysis, tools like FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis) and DOE (Design of Experiments) may be used. The key is to choose the right tool for the job: PDCA and DMAIC are overarching improvement methods, while others like 5 Whys, Gemba, or control charts are specific techniques within those methods.

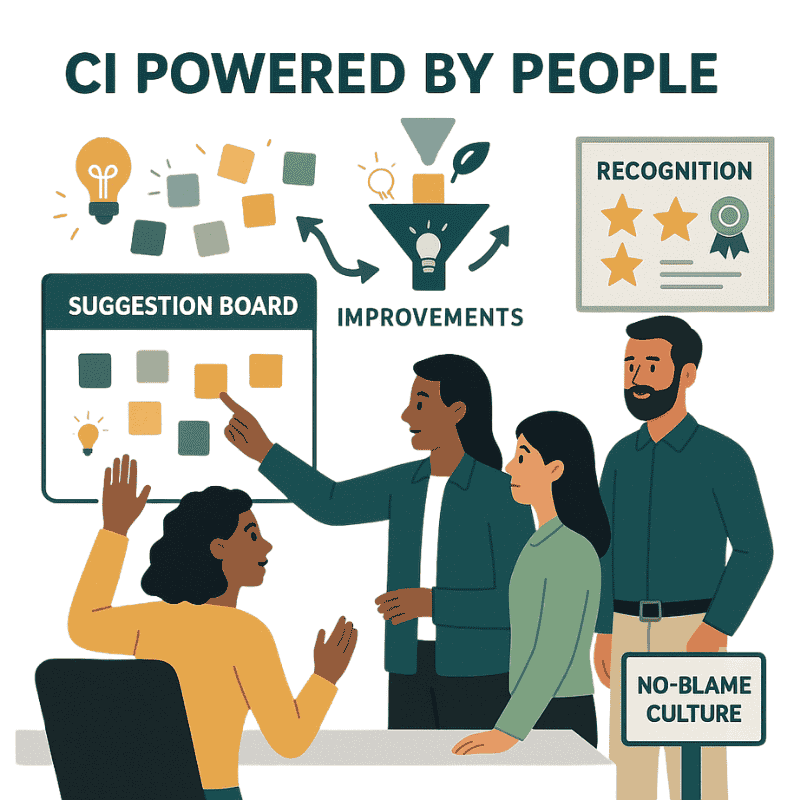

Building a CI Culture: Leadership, Training, and Employee Engagement

Continuous improvement depends most of all on people and culture. A thriving CI culture involves committed leadership, skilled teams, and engaged employees at all levels.

Leadership and Vision

CI must be driven from the top. Executives and managers need to champion CI and embed it into the company’s values. This means visibly participating in improvement activities, allocating resources, and recognizing teams’ efforts. Lean thinkers emphasize that leaders should spend time on the floor and lead by example. Toyota’s Fujio Cho (former chairman) summed it up: Lean leaders should “go see” the actual work, “ask why,” and “show respect” to the people doing the work. When leaders follow this counsel, they demonstrate that improvement is as important as any production goal. Regular management reviews of CI metrics (e.g. savings from Kaizen events, number of improvement ideas implemented) also keep the focus on continuous improvement.

Leadership must also align CI with strategy and long-term vision. As one HBR case noted, health systems that applied TPS gained big improvements in quality and cost by redesigning processes, but when the champion leader left, those gains eroded. This shows that leadership commitment must be sustained. Organizations should avoid depending on a single CI “hero”; instead, they establish structures (like Lean Six Sigma councils or Hoshin planning) so improvement continues even if people change. In short, leaders set the tone for CI. They must communicate a clear improvement strategy, remove obstacles, and balance short-term goals with the ongoing pursuit of excellence.

Training and Skill-Building

Employees need training and skills to participate effectively in CI. This includes teaching the methods (e.g. PDCA, DMAIC), tools (e.g. control charts, root-cause analysis), and problem-solving approaches (fact-based analysis, 5 Whys). Many organizations use formal Lean or Six Sigma training programs (Green/Black Belts) to develop internal experts. For example, one study of hospitals found that a multidisciplinary team approach coupled with Six Sigma training was critical to successful CI implementationasq.org. Training builds a common language and rigor around improvement. It also empowers employees: when workers know how to analyze data or run a Kaizen event, they can drive more effective changes.

Training should be continuous and broad-based, not just for a few champions. Regular workshops, on-the-job coaching, and e-learning can help spread CI know-how. It’s also important to teach leadership and teamwork skills (for CI coaches) and basic problem-solving for all staff. The Lean Six Sigma principles emphasize that employee involvement is crucial – which means team training must go hand-in-hand with engaging employees’ ideas.

Empowering Employees

Arguably, the most important ingredient in CI culture is employee engagement. Everyone in the organization should feel responsible for improvement. The Kaizen philosophy explicitly involves all employees in the CI process: workers at every level are encouraged to spot inefficiencies and propose practical solutions. In practice, this might take the form of suggestion programs, daily team huddles, or Kaizen improvement events where staff tackle a problem in one area each week.

When employees are engaged, CI becomes bottom-up as well as top-down. Front-line workers know the details of their processes and can often identify root causes faster than management. Lean Six Sigma principles note that “employees are a valuable knowledge source on processes” and that encouraging their active participation “helps pinpoint improvement opportunities”. Companies like Toyota institutionalize this by asking each worker to continuously improve their own workspace or process.

To empower employees, organizations should foster a no-blame culture. Mistakes and problems should be treated as learning opportunities. For example, the 5 Whys method explicitly warns against assigning fault to individuals; instead, it focuses on systemic causes. Recognition programs (awards, public acknowledgment) for great improvement ideas also motivate participation. In summary, a CI culture thrives when all employees are involved in problem-solving, supported by leadership respect and a sense of shared responsibility.

Real-World Case Studies and Examples

Lean manufacturing has revolutionized operations in companies large and small. The classic example is Toyota Motor Corporation itself. Beginning in the 1950s, Toyota developed the Toyota Production System by applying lean principles on its assembly lines. Toyota’s objective was “to thoroughly eliminate waste and shorten lead times” so that every vehicle could be made faster, cheaper, and with higher quality. Over decades, Toyota embedded kaizen into its culture; every worker participates in daily improvement activities. The results are legendary: Toyota became one of the world’s most efficient and profitable manufacturers, with defect rates far below industry norms and production lead times reduced dramatically.

Other manufacturers have seen powerful results from lean:

- Boeing (Aerospace): When Boeing adopted lean in the late 1990s, it transformed airplane production. An EPA analysis reports that Boeing’s lean initiatives led to 30–70% gains in resource productivity. By reorganizing factories into product-focused lines and applying value-stream thinking, Boeing slashed waste and energy use. The company now continually improves flow and quality: even pre-1996 lean efforts, Boeing expanded lean across the company after “early successes in the endeavour”. Lean has helped Boeing reduce costs, cut cycle times, and improve responsiveness to customers.

- Harley-Davidson (Motorcycles): In the 1980s, the motorcycle maker famously turned its business around by implementing lean (as described in the book The Machine That Changed the World). Harley integrated just-in-time inventory, U-shaped manufacturing cells, and employee-driven problem solving. These changes reduced production lead time from 21 days to 1 day, while boosting quality and saving millions.

- Virginia Mason Medical Center (Healthcare): Although not manufacturing, this hospital applied the Toyota Production System to healthcare. By using value-stream mapping and daily Kaizen (called “Value Stream Events”), Virginia Mason greatly reduced patient wait times and medical errors, illustrating how lean’s principles of waste elimination and continuous improvement have cross-industry impact.

- Intel (Technology): Semiconductor plants use lean to keep huge chip-fabrication facilities running efficiently. Intel has employed pull systems and SMED to reduce downtime during product changeovers, increasing capacity and yield.

- General Motors and Ford (Automotive): U.S. automakers have adopted lean with notable success. For example, Ford’s Virginia plant cut new-model launch time by 50% using lean-work cells, and GM plants around the world have implemented lean production with multi-million-dollar savings.

These examples demonstrate that any organization can benefit from lean – from heavy industry to services. A 2013 EPA report on lean notes, “Substantial research… indicates that American industries are actively implementing Lean Manufacturing as a key strategy for remaining competitive”. Wherever it’s applied, lean drives continuous gains: as one Toyota expert put it, lean produces a “culture of waste elimination” in which each improvement leads to the next.

Conclusion

Continuous improvement is a strategic philosophy and culture that can drive lasting performance gains. By combining Lean thinking (waste elimination and flow), Kaizen (small daily improvements), and Six Sigma (data-driven defect reduction), organizations can systematically optimize their processes. Key tools like PDCA, DMAIC, the 5 Whys, Gemba walks, and control charts provide structured approaches to problem solving.

When CI is embedded in an organization’s strategy and culture, the results can be transformative. For example, Motorola documented over $16 billion in savings through Six Sigma initiatives, and numerous hospitals have significantly reduced wait times and costs with Lean Six Sigma. These gains come from empowering employees to constantly seek better ways of working, with strong leadership support.

To learn more about continuous improvement, readers can consult the Lean Enterprise Institute (lean.org) for Lean and Kaizen case studies and lexicon terms, ASQ (asq.org) for quality improvement resources and Six Sigma guides, and Harvard Business Review articles on Lean thinking and culture. Important books include Masaaki Imai’s “Kaizen” on continuous improvement, “The Toyota Way” by Jeffrey Liker for Lean principles, and Six Sigma handbooks on the DMAIC methodology. In summary, CI is an ongoing journey: by cultivating a lean management culture of respect and learning, and by using CI tools consistently, organizations can achieve continuous process optimization and sustainable excellence.

Further Reading: Lean Enterprise Institute (Lean.org) Kaizen, ASQ Quality Resources, and Harvard Business Review on Lean and CI.

References

- ASQ. (n.d.). DMAIC: Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control. [online] Available at: https://asq.org/quality-resources/dmaic [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- ASQ. (n.d.). What is Continuous Improvement?. [online] Available at: https://asq.org/quality-resources/continuous-improvement [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- Chandrasekaran, A. and Toussaint, J. (2014). How the World’s Best Hospitals Learn from Toyota. Harvard Business Review. [online] Available at: https://hbr.org/2014/10/how-the-worlds-best-hospitals-learn-from-toyota [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- Imai, M. (1986). Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s Competitive Success. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lean Enterprise Institute. (n.d.). Kaizen. [online] Available at: https://www.lean.org/lexicon/kaizen [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- Lean Enterprise Institute. (n.d.). What is Lean?. [online] Available at: https://www.lean.org/whatslean/ [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- Lean Enterprise Institute. (n.d.). Lean Culture. [online] Available at: https://www.lean.org/lexicon/lean-culture [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- Leanscape.io. (n.d.). What is a Gemba Walk?. [online] Available at: https://leanscape.io/gemba-walk/ [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- Motorola University. (n.d.). Six Sigma Savings and Benefits. [online] Available at: https://www.motorolasolutions.com [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- StatCounter. (2025). Search Engine Market Share Worldwide. [online] Available at: https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- Toyota Global. (n.d.). The Toyota Production System. [online] Available at: https://global.toyota/en/company/vision-and-philosophy/production-system/ [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- Verble, D. (2014). What is a Lean Culture? Lean Enterprise Institute. [online] Available at: https://www.lean.org/the-lean-post/articles/what-is-a-lean-culture/ [Accessed 2 May 2025].

- Virginia Mason Institute. (n.d.). Lean Healthcare Transformation. [online] Available at: https://www.virginiamasoninstitute.org [Accessed 2 May 2025].